CAP Theorem Explained: Beyond the "Pick Two" Myth

Let's get to the bottom of what Consistency, Availability, and Partition Tolerance actually mean in production distributed systems.

Hey folks, I’m back. I haven’t posted in a while, I know, I know. Between work, life, and the usual "is anyone even reading this?" doubt spiral, I let this blog collect dust. But I'm back with a new approach.

Instead of sporadic posts on random topics, I’m committing to deep-dive series on fundamental concepts that I wish I understood better earlier in my career. Technical content that goes beyond the interview answer and into the real production trade-offs.

This four-part series on CAP theorem is the first of many deep dives I have planned. If you’ve ever felt like you “get” distributed systems in theory but struggle to apply that knowledge in practice, this series is for you.

Thanks for sticking around (or for just discovering this blog). Let’s learn together.

This is Part 1 of a 4-part series on CAP theorem and distributed systems trade-offs. Part 2 drops next week.

If you’ve interviewed for mid or senior-level engineering roles within the last decade, you’re sure to have been asked a systems design question that ultimately leads to some version of the CAP theorem. And you probably answered something along the lines of “you can only pick two of three”. You were right…kinda.

While it’s technically correct, the thought behind it is grotesquely oversimplified. That oversimplification comes back to bite you when you’re debugging why your distributed data store went down.

My goal is to demystify what the CAP theorem tells us and explain how production systems get around this “pick two” crutch.

What Is The CAP Theorem?

Let’s go back to the turn of the century, in 2000, Eric Brewer, then running Inktomi Corporation, stood at the podium of ACM’s PODC symposium and made a statement that would trouble developers for decades: a distributed data store can only guarantee at most two of the three of the following: Consistency, Availability, and Partition Tolerance.

A couple of years later Brewer’s theorem was formalized into a proof by Seth Gilbert and Nancy Lynch. The theorem, the idea behind it, everything is true. But somewhere in the last two decades between all of the whiteboard sessions the nuance got lost.

What’s the nuance you ask? Well everyone remembers the “pick two” portion of the conjecture but they almost always leave out the most important context: you only have to pick two during a network partition.

When the network is healthy, you can have all three. The theorem provides guidance only when things go awry—when you start losing network packets, or switches fail, or when a rodent chews through a fiber line (this has actually happened at Amazon).

CAP Theorem: Consistency, Availability, and Partition Tolerance Defined

Let’s be super precise about what C, A, and P actually are and what they mean, because the casual definitions lack a bit of nuance.

What Is Consistency in CAP Theorem? (Linearizability)

When the CAP theorem talks about consistency, it’s talking about the highest form of consistency, atomic consistency. If you’re coming from a database background, you’ve heard of weak and strong consistency. Atomic consistency is just a step above strong consistency. Atomic consistency is also known as linearizability.

Linearizability is when all operations execute atomically in some order with respect to real-time. For example, if operation A completes before operation B begins, then operation B should logically take effect after operation A.

Let’s use a real world example to help illustrate this idea. Imagine you’re checking your bank account balance and you see $5000. Let’s say you transfer $1000 out of the account. Now you refresh your balance again. Linearizability guarantees $4000 (or an error), but never $5000 again. The transfer either happened or it didn’t. There’s no situation in which you will see the old value after the new value has been written.

This is a lot stronger than “all nodes eventually see the same data” — this is called eventual consistency and it is NOT what the CAP theorem is talking about.

Why is this important? Because there are a bunch of systems that provide weaker consistency models, such as: monotonic reads, read-your-writes, and causal consistency, while being extremely useful. But all of those models are weaker than linearizability, which means systems can remain highly available while providing them. The CAP theorem doesn’t constrain systems using these models, only linearizability.

What Is Availability in CAP Theorem?

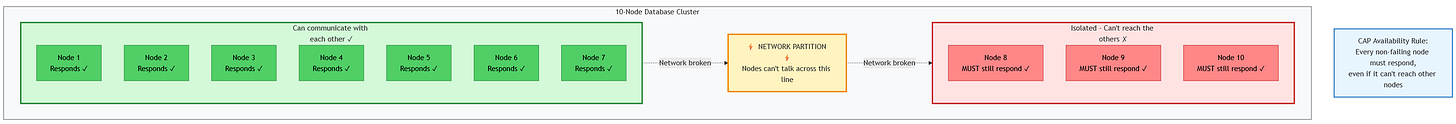

CAP’s definition of availability is also very precise, it states “every request to a non-failing node must receive a response”.

Notice that this doesn’t say any of the following:

That the response has to be fast.

That the response has to be correct.

That most nodes have to respond.

For example, if you have a 10 node cluster and 4 of those nodes are partitioned away, those 4 nodes must still respond to requests to be considered “available” under CAP’s definition of “availability”. In this case a 4xx error or a stale read still counts as “available”.

Here’s a real world example: During a network partition, a MongoDB primary replica set that can’t reach all of the secondary replicas will “step down” and refuse writes altogether. These write requests will time out. Under the CAP theorem that is unavailability, even though the MongoDB process is running as expected.

What Is Partition Tolerance? (And Why You Can't Avoid It)

This is where the “pick two” framing stems.

Partition tolerance means that your system continues to work as advertised even when the network splits your nodes into groups that can’t communicate. Guess what? This isn’t up to you.

Network partitions are a fact of life in distributed systems. The internet that we rely on daily, the data centers that serve our applications all have this property. Switches fail, fibers get cut, cloud providers have availability zone outages, packets get dropped, even within a data center there are transient network issues. It’s unavoidable.

The reality is, partition tolerance is absolutely mandatory. You’re not picking between C, A, and P. You’re really picking between C and A when P inevitably occurs.

The Real Trade-off

Okay let’s observe what happens when the network eventually fails.

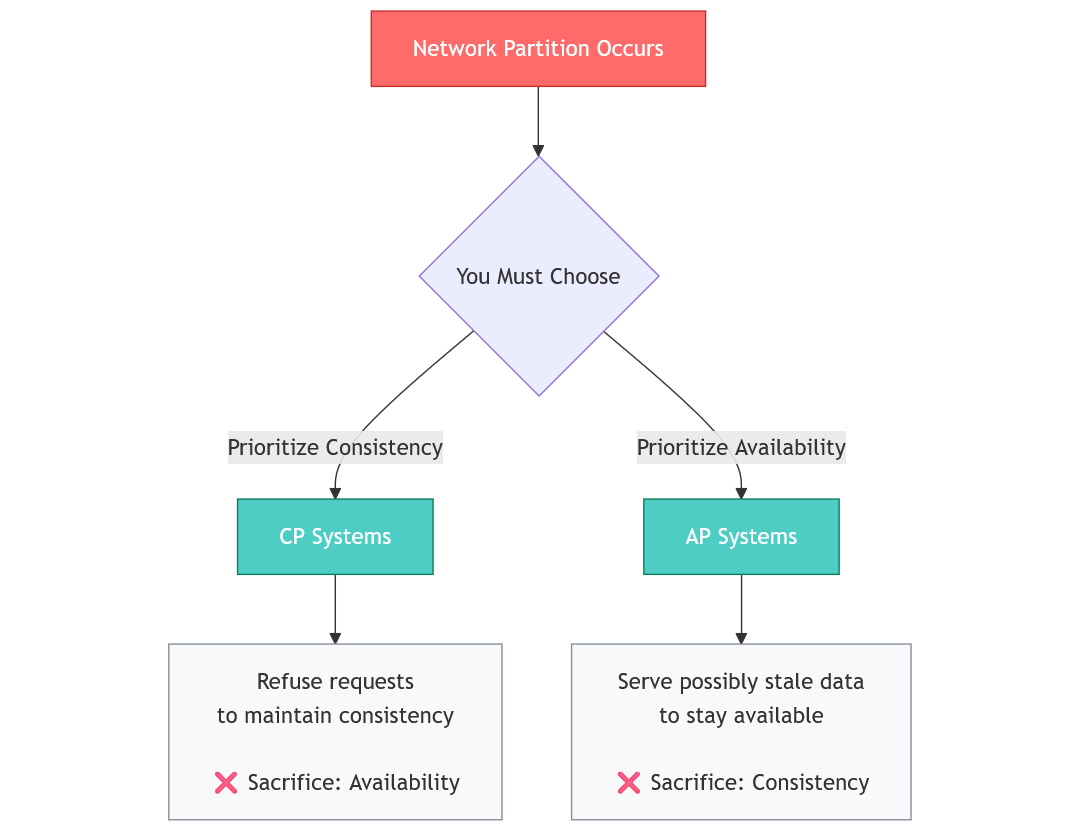

Before doing so, let’s rephrase the CAP theorem and its choices given that P (Partition Tolerance) is absolutely mandatory:

Consistency: refuse requests that might return stale data (sacrificing availability)

Availability: answer all requests even if data is stale (sacrificing consistency)

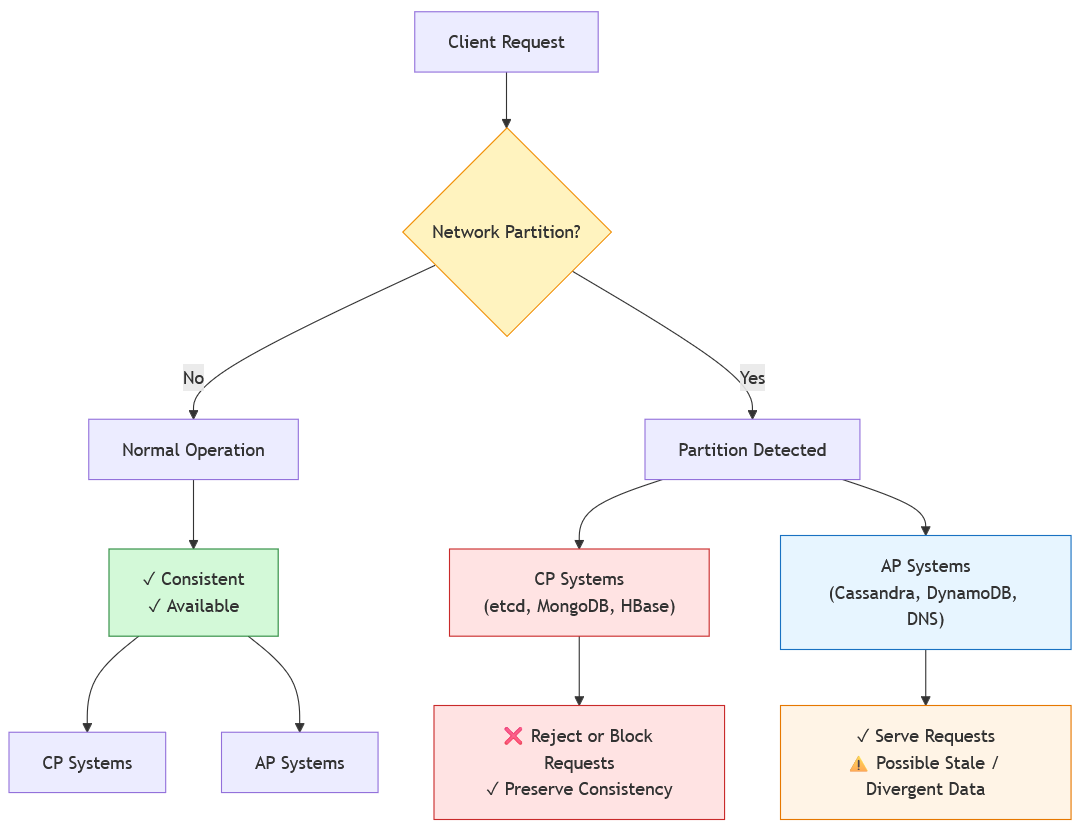

Once again, take note of the precondition; “when the network fails”. If the network is fine we can have both consistency and availability. When there's no partition? You can have both. Your bank's mobile app shows you accurate, up-to-date balances while staying highly available—because most of the time, the network works fine. You check your balance, transfer money, and see the updated amount immediately.

The question the CAP theorem forces you to address is: What should your system do when the network eventually fails?

The core trade-off: During a partition, CP systems protect you from seeing wrong data by becoming unavailable. AP systems protect you from downtime by potentially serving stale data. Neither is good or bad, it all depends on what is right for your system.CP Systems: Choosing Consistency Over Availability

CP systems decide that during a network partition, they’ll refuse requests rather than risk returning outdated data.

So when does this make sense?

Banks: If a user makes a transaction is it preferable to be down for a little bit or risk the transaction occurring twice? Probably the former right? We absolutely do not want to tell the customer that the transaction succeeded when it hasn’t. We’d rather be down for like 30 seconds than risk that.

Inventory Management: if we’re not sure whether an item is in stock, is it better to make the service unavailable or to allow the possibility of over-selling? We’d probably be okay with unavailability.

Let’s analyze a real-world system, etcd. From their own website: “etcd is a strongly consistent, distributed key-value store…It gracefully handles leader elections during network partitions and can tolerate machine failure, even in the leader node.”

Kubernetes uses etcd as its backing store for all cluster configurations. If you’ve used Kubernetes before, you’ve seen kubectl command failures. One reason: etcd can’t reach a majority of its nodes, it sacrifices availability (kubectl failures) for linearizability.

AP Systems: Choosing Availability Over Consistency

AP systems decide that during a network partition, they’ll risk serving stale data rather than deny requests.

A few systems that this applies for:

Social Media Feeds: users would much rather the app serve old / stale content rather than be completely unavailable. Additionally, does it really matter if a user doesn’t see a reaction to their post for a couple of seconds? Not really. The user experience of the app being down is far worse than reaction tallies being off.

Shopping Carts: A very famous example of this is Amazon’s DynamoDB which actually started off addressing their shopping cart problem; it’s an “always on” experience. You can always add to cart. Doesn’t matter if someone else is fiddling with your cart (Amazon will resolve the changes), you will always be able to “add to cart”.

For a real-world AP system you don’t have to think very hard, the most pure AP system is none other than DNS itself. DNS, the Domain Name System, is the perfect example of an AP system and we all use it hundreds of times a day without even realizing it.

When a DNS record is updated, the update doesn’t propagate to every DNS server around the world immediately. Different DNS servers around the world may give an outdated DNS entry, however, DNS is never “unavailable”. It will always give you a response, even if that response is stale. This is exactly why DNS updates take time and why some sites appear unavailable to a few people when going through updates. In the case of DNS, eventual consistency is absolutely better than downtime, that would kill the internet.

Next Up: The Hidden Costs of Choosing Consistency

In the next part of this series, we'll dive deep into CP systems—databases and services that prioritize consistency over availability during network failures. We’ll take a look at:

How these CP systems implement strong consistency.

The cost of coordination.

When choosing consistency over availability makes sense.

The “pick two” gives the illusion of being stuck with your choice for the entire lifetime of the system, when in fact the reality is a lot more flexible.

Thanks again for sticking around. If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe, it gives me the confidence to keep going.

Ali