CP Systems Explained: The Hidden Cost of Strong Consistency

Let's look at what CP systems actually do under the hood when they choose consistency over availability.

Let’s look at what CP systems actually do under the hood when they choose consistency over availability.

This is Part 2 of a 4-part series covering the CAP theorem and distributed systems trade-offs. If you haven’t done so already, read Part 1 here!

In Part 1, we examined the CAP theorem holistically and its “pick two” myth. We narrowed the CAP theorem down to this singular question: what should your system do when the network fails?

CP (Consistency, Partition Tolerant) systems answer this question with: “I’d rather be unavailable than wrong.”

That’s fine and all, but choices have consequences. Consequences don’t always show up easily, sometimes it’s 2 AM on a weekend when you realize your system is taking entirely too long to write to a database.

Requisites of a “CP” System

As we defined earlier, a CP system is one that prioritizes “consistency” over “availability” during network partitions. What does that look like in the real-world?

Blocked Writes

What this means is, if you attempt to write to your system during a network partition, it will not be acknowledged / confirmed until it’s been replicated to enough nodes. “Enough” is subjective but typically means a majority (i.e 2 of 3 or 3 of 5), this is also referred to as the quorum.

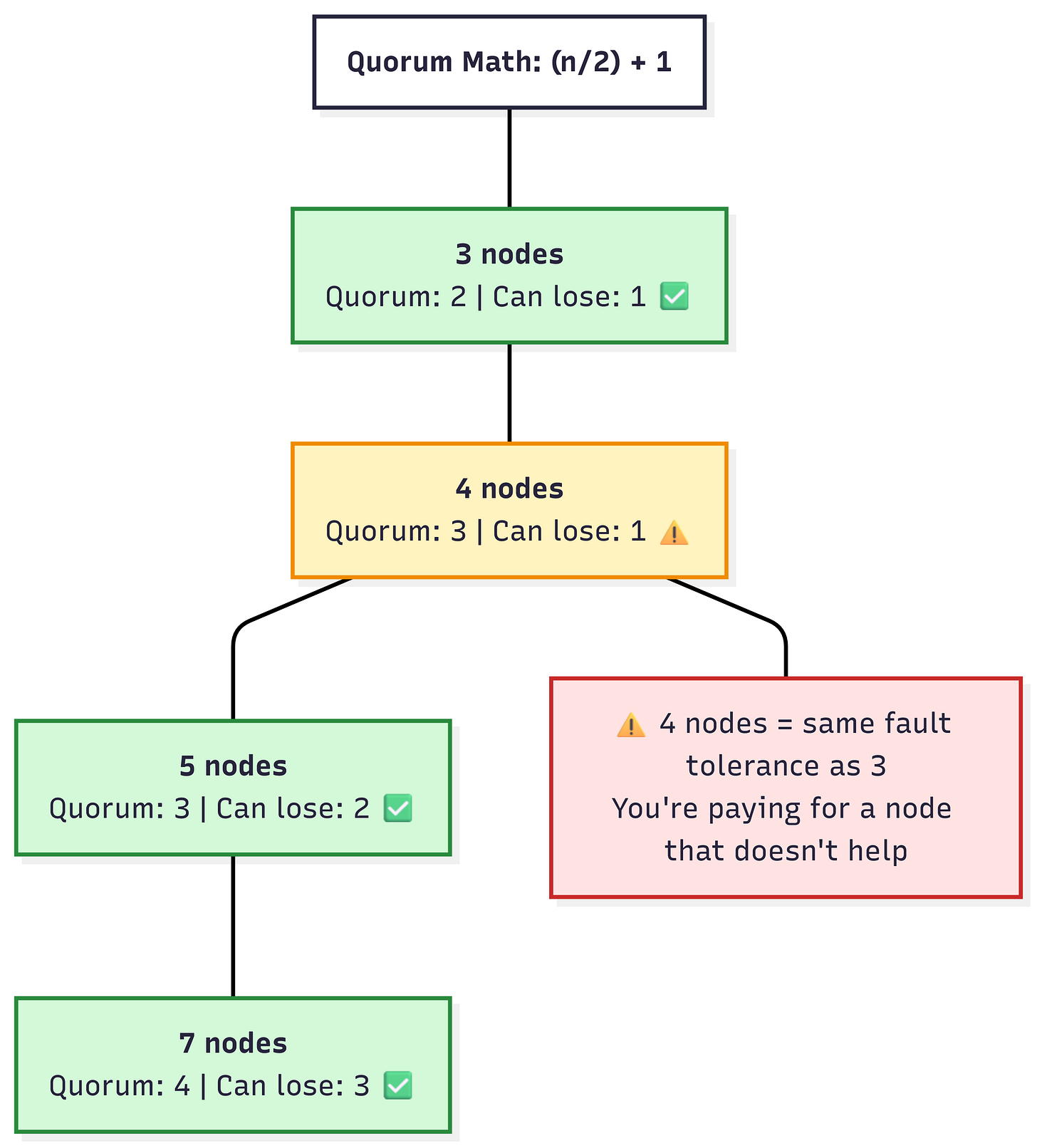

Always use odd numbers. A 4-node cluster has the same fault tolerance as a 3-node cluster—you’re paying for a node that doesn’t improve availability.

Going back to etcd, a kubectl apply will not return until at least half of the cluster confirms the write. Similarly, in a Postgres setup with synchronous replication enabled, an INSERT waits for the replicas to confirm that the data was received and written.

And this is exactly why writes are slower in CP systems. You are no longer just writing to a single node and moving on, you have to wait for network round trips and the slowest node in the quorum.

Most Up-to-Date Reads

CP systems can guarantee fresh reads when using linearizable or quorum-backed read modes You will never read stale data. If you just wrote a value, you’ll read that very value back, or get an error (as shown above, if quorum isn’t met). In MongoDB if you enable linearizable read concern, your reads will go to the primary and wait to confirm that there aren’t any other writes in progress. Back to our etcd example, you can read from follower nodes but the default logic guarantees that you do not read anything that hasn’t been committed to quorum.

As before, what’s the cost for strong consistent reads? It’s read latency. You can’t simply fetch data from the fastest / nearest replica, there’s a robust level of coordination involved that ensures you’re always getting the freshest data.

Partitioned Nodes Stop

In CP systems, if a node can’t reach its peers it’ll refuse requests outright rather than risk returning stale data. There’s no guessing involved, it simply will not serve stale data.

What does this mean in practice? The node will return an error or simply timeout. Going back to MongoDB, if the primary node can’t reach its secondaries, it will step down as the primary and refuse writes altogether. In the case of etcd, if the node gets partitioned away, it’ll stop accepting requests until it rejoins the cluster.

What Happens During a Partition?

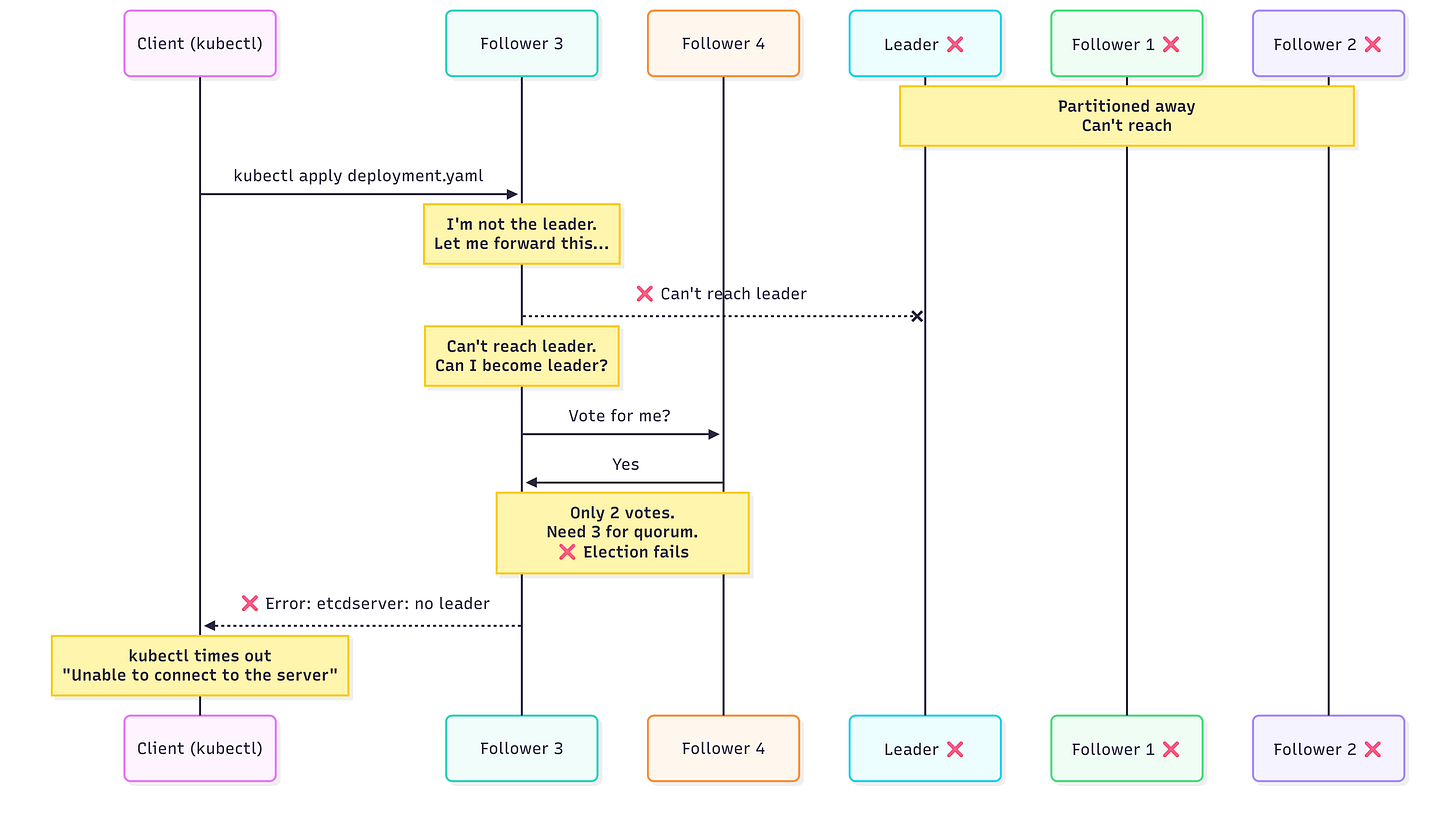

Let’s walk through a concrete example of a network partition that’ll help visualize all of the above.

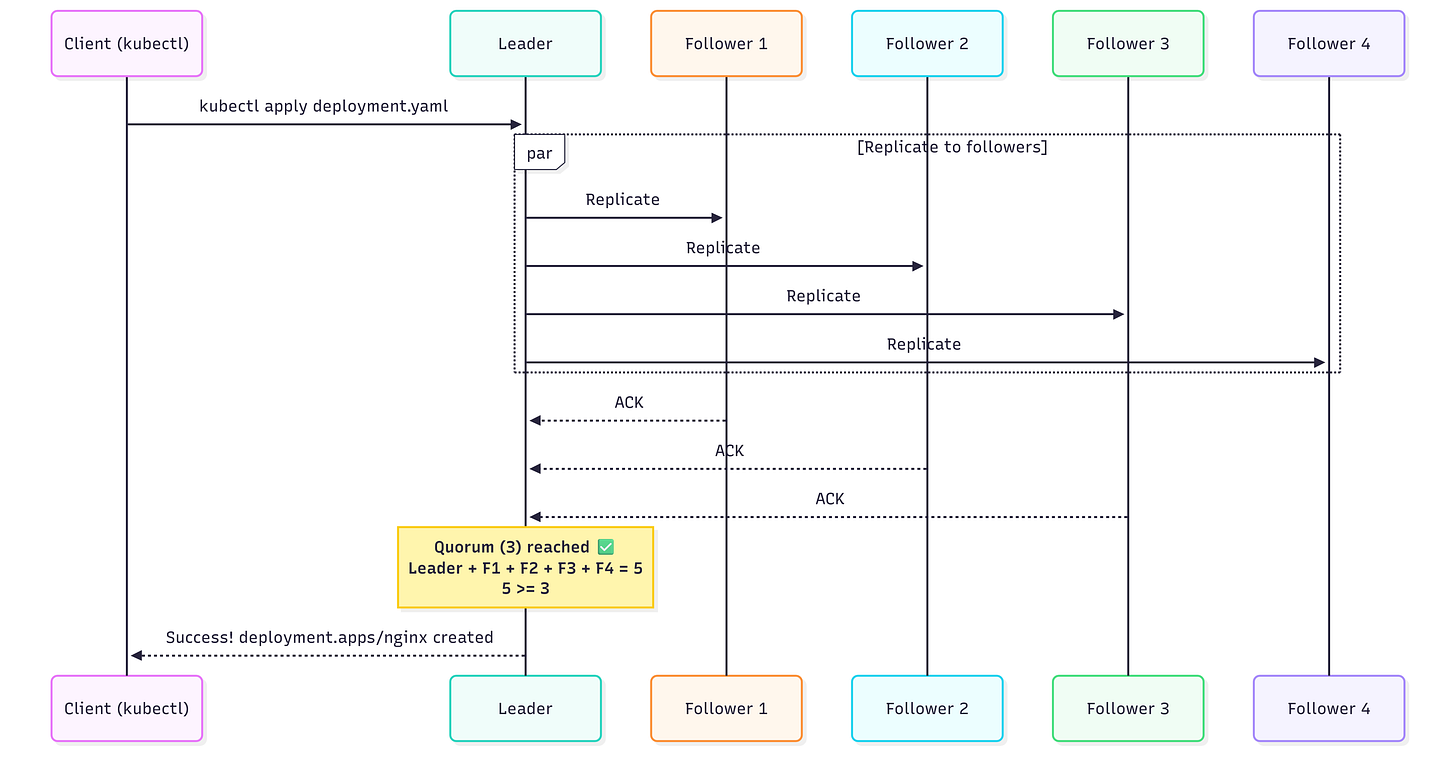

Let’s assume we have 5-node etcd cluster with a quorum of 3. Everything is running perfectly, writes go to the leader, get replicated to followers, quorum is reached, and clients are happy.

Everything is working. Writes go to the leader, get replicated to followers, clients are happy.

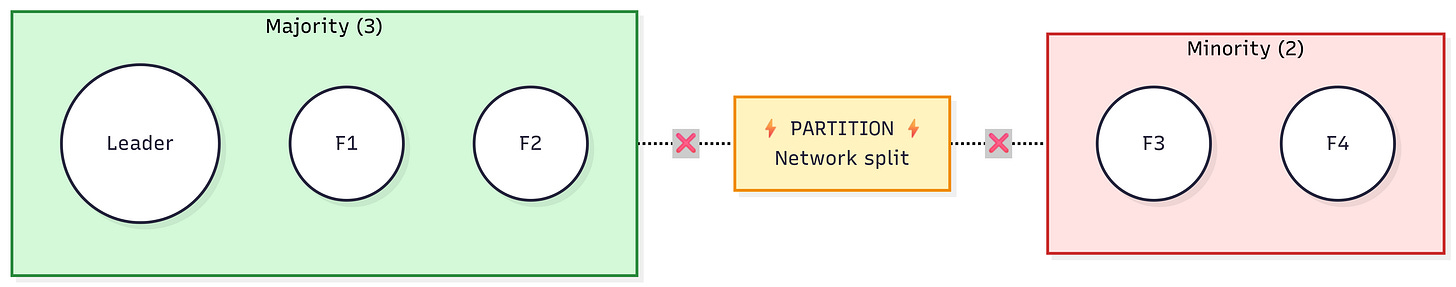

Then a network partition splits the cluster in a 3-2 configuration. Three nodes can still communicate with each other. Two nodes are isolated.

Majority Side

There is still quorum (3 of 5).

If necessary, a new leader is elected and operations continue.

Both writes and reads succeed.

Clients connected to any node in this majority side experiences absolutely nothing out of the ordinary.

Minority Side

Can’t reach quorum (2 < 3)

Writes are refused.

Depending on how the system is configured, reads are also refused.

Clients connected to this side see timeouts / errors.

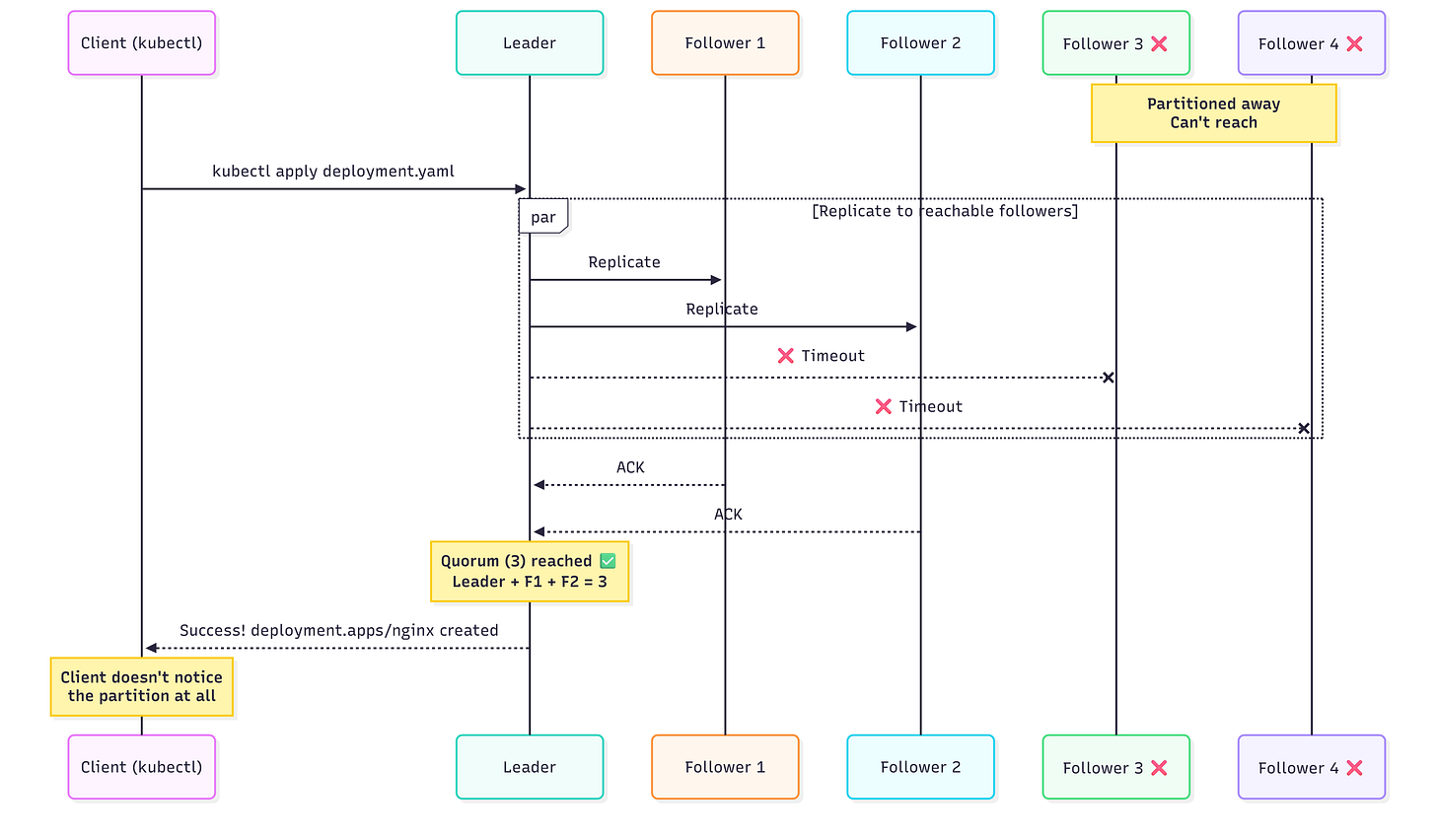

Clients connected to the majority side don’t notice anything. Writes still work because quorum (3) is reachable.

Clients connected to the minority side see timeouts and errors. The nodes refuse to serve requests because they can’t reach quorum.

This is what CP systems look like in action. The minority side (nodes that have been partitioned away) don’t return stale data. There’s no guess work, the nodes simply don’t respond. Eventually, when the partition heals, all nodes sync up with the majority side and behave normally again.

Sure this is cumbersome when you’re the client connected to the minority side, but this is what guarantees you data “consistency” (remember, what we mean here by consistency is actually linearizability).

The Costs of Linearizability

As we’ve shown thus far, nothing is free in systems. CP systems pay for linearizability with latency, availability, and operational complexity. Why? Because consensus is expensive.

A Quick Primer on Consensus Protocols

What problem have we identified thus far? CP systems need nodes to agree on the state of data. Easy when everything is going well, but given the unreliable nature of networks this is harder than it sounds.

There are two main protocols that allow multiple machines to achieve consensus: Paxos and Raft.

Paxos

Paxos is the original consensus protocol. Created by Leslie Lamport in 1989, Paxos is notorious for being difficult to understand (the original paper’s title should be enough proof of that).

Paxos guarantees three properties:

Validity: Only values that were actually proposed can be chosen. There’s no randomness and no garbage.

Agreement (Consensus): All nodes that reach a decision will reach the same decision. No two nodes can come to different decisions.

Integrity: Once a value is chosen, it’s permanent. There’s no un-choosing.

Basically, nodes go through multiple rounds of voting to agree on a specific value. Once a value is chosen it can never be un-chosen, regardless of what happens.

These guarantees hold even throughout node crashes, message loss, and packet delays. Paxos never compromises on safety. The downside? Paxos can’t guarantee liveness. Under some conditions (competing proposers, network issues), Paxos can stall indefinitely. It won’t return a wrong answer, but it might just not answer altogether (do you want to be right all the time or do you want to respond all the time). In production systems this is very rare, techniques like random backoffs and leader election help some of this, but it’s important to note that this is a trade-off in the protocol itself.

In the real world, Paxos is very difficult to implement properly which led to alternatives. Many systems you’ll encounter in the real world use Raft instead of Paxos.

Raft

Raft was created in 2014 with one goal in mind: comprehensibility. The authors of the Raft paper (In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm) quite literally ran user studies that showed that Raft was easier to understand and comprehend when compared to Paxos.

Raft, like Paxos, provides the same three guarantees: validity, quorum-based agreement, and integrity. But Raft, to make the protocol more understandable, breaks them into three separate problems:

Leader Election: Only one leader per term (time period). All writes go through this leader.

Log Completion: If an entry is committed, it will be in all future leaders’ logs.

Safety: A committed write will never be lost, even if the leader goes down.

Similar to Paxos, Raft requires a majority quorum to make decisions. Like our previous example, in a 5-node cluster, you’d need 3 nodes to agree. If you can only reach 2 nodes, the system would stop accepting writes.

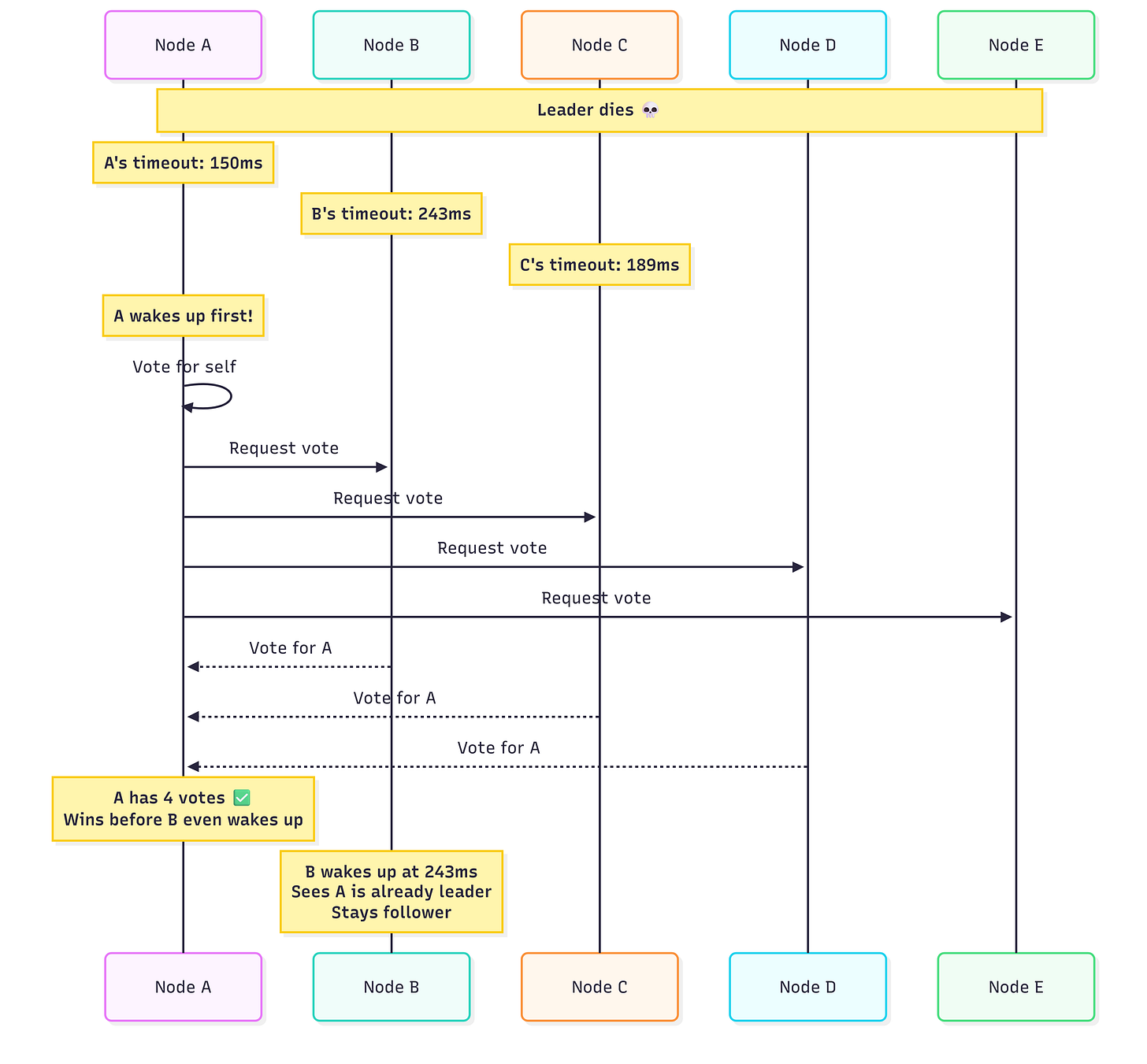

The liveness problem is addressed with randomized election timeouts. When a leader dies, followers wait a random amount of time before conducting an election. This makes split votes (where no candidate is able to reach quorum) rare in practice.

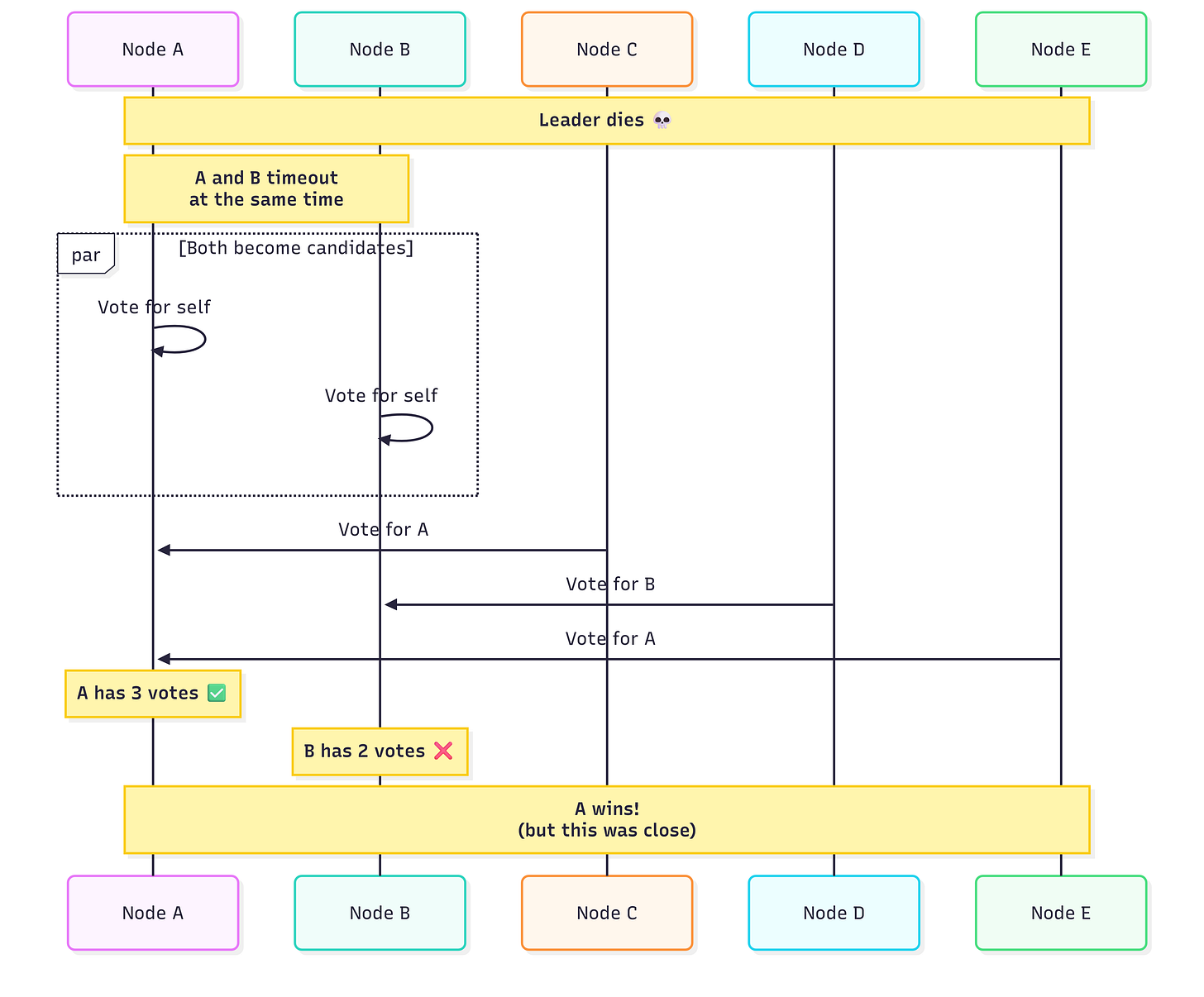

Let’s see the liveness problem visualized.

Two nodes timeout simultaneously and both become candidates. This time A squeaks by with 3 votes, but it was close. If one more node had voted for B, we’d have a split.

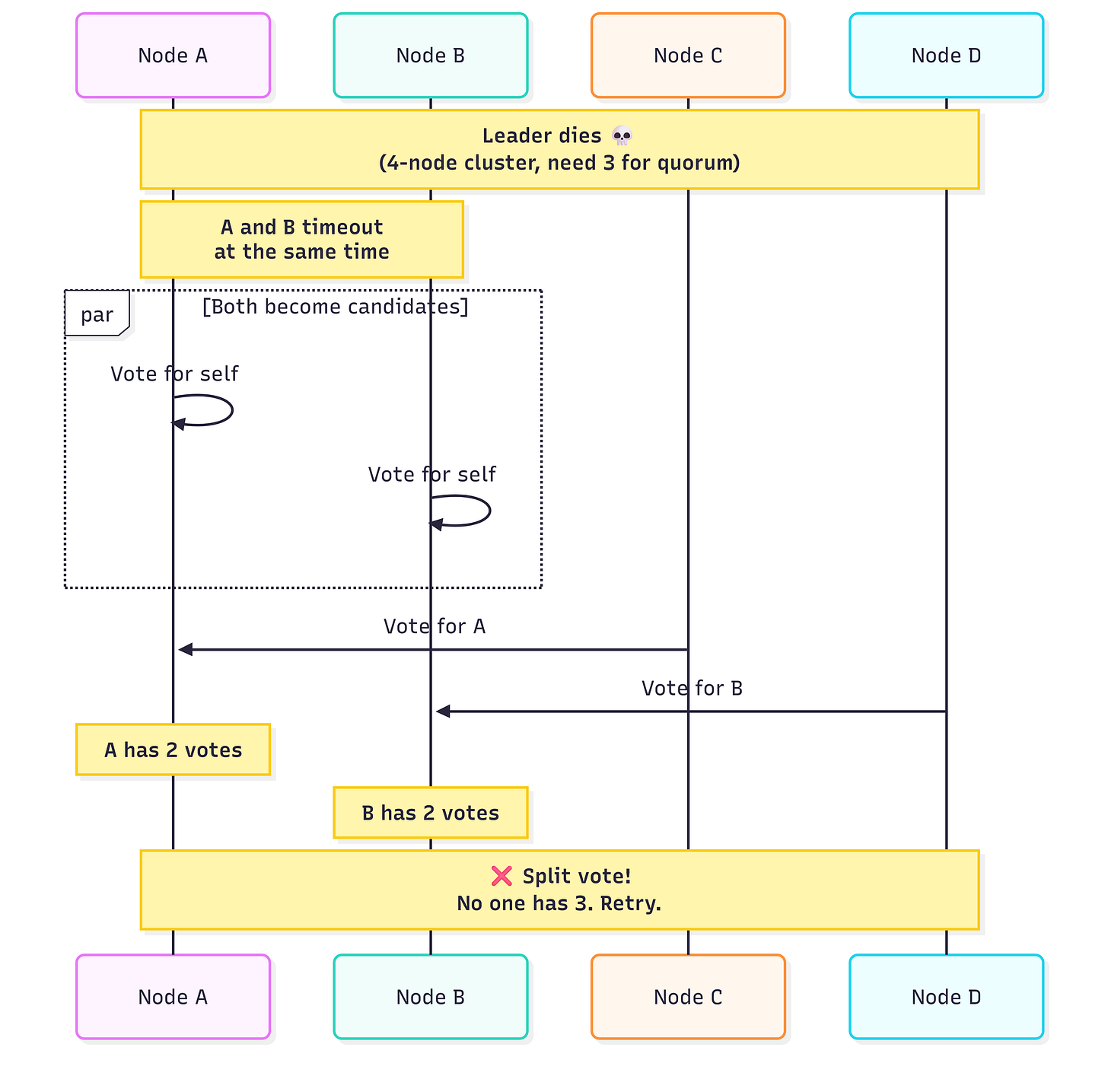

The worst case. Votes split evenly, no one reaches quorum. The cluster has to wait for timeouts to expire and try again. If this keeps happening, you’re stuck without a leader.

Randomized timeouts fix this. Each node picks a random timeout (e.g., 150-300ms). Node A wakes up first at 150ms and campaigns unopposed. By the time B wakes up at 243ms, A is already leader. No split, no drama.

One problem both Raft and Paxos share is that neither handles Byzantine faults. Both protocols assume nodes to be honest.

I’ll save the deep-dive into Raft / Paxos internals for another post. For now all you need to understand is: consensus requires coordination, and coordination is very costly.

The Costs of CP Systems

Here’s something that the CAP Theorem fails to mention: even when there is no partition, CP systems pay a performance price.

Latency

Every write requires a confirmation from multiple nodes. In our example of a 5-node cluster, a single write requires 3 confirmations. That’s at least 3 round trips before a write is acknowledged.

If the nodes are in the same data center, latency is a few milliseconds. However, if the nodes are geographically separated, that latency shoots up to anywhere between 5-200ms, per write.

That’s why when designing CP systems geographic placement of nodes is important. Global distribution and strong consistency don’t mix well.

Consensus hates distance. For CP systems latency is equivalent to the slowest node you must wait for not the average node latency. So in our 5-node cluster, a write requires 3 nodes to agree. The latency for that write is the latency of the slowest member of the agreeing nodes.

Throughput

Since all writes flow through a single leader, you can only write as fast as that leader can process and replicate. The leader is responsible for serialization, ordering, and coordinating replication. With multiple writes, CPU, network, and disk resource contention accumulates.

How do we increase throughput? If you said scaling you’d be right….partially. Horizontal scaling doesn’t help. Actually, it might be more of a pain. Adding more nodes increases coordination overhead. Past a certain point, horizontal scaling actually makes you slower. So, we vertically scale. Even then, there are cons to vertical scaling.

Scaling vertically makes CPU, memory, and disk i/o faster. But it does not lower network round-trip times.

There is a throughput ceiling for CP systems. Throughput is directly related to the round-trip time for quorum and the ordering capacity of the leader.

Leader Election Storms

When the leader node dies, the cluster elects a new one. Each election causes:

Coordination overhead as nodes ask for votes and reply.

Service disruption while the cluster, effectively, pauses to elect a leader.

Instability as nodes switch roles and reset timers.

Elections are annoying. If two nodes start campaigning at the same time, votes can split and no one reaches quorum. Raft uses randomized timeouts to avoid this, but under network jitter or heavy load, you can still get stuck in multiple rounds of failed elections.

If you’ve used Kubernetes before, you may have run into issues where etcd completely stops responding and it isn’t your doing.

Let’s go back to our 5-node etcd cluster (Nodes A-E) example, let’s say your cloud provider’s network hiccups for 500ms, just long enough for the leader to lose contact with 2 followers. It steps down. Election happens, Node B wins. 200ms later, another blip. Node B can’t reach quorum now. Steps down. Another election. This keeps going while kubectl commands pile up in the background. Network stabilizes, you check the logs, and realize you just burned 30 seconds on 3 elections.

Operational Complexity

CP systems are very hard to implement. An added layer of complexity is capacity planning.

Odd Number of Nodes: a 4-node cluster and 3-node cluster have the same fault tolerance (losing two nodes will render the system unavailable since quorum can’t be met). So adding a single node doesn’t really help in this case.

Quorum / Fault Tolerance Math Matters: A 5-node cluster needs 3 nodes for quorum, meaning it can withstand 2 nodes going down. A 3-node cluster needs to 2 nodes for quorum, meaning it can handle only one node going down.

Failure Pains: CP systems behave correctly under failure, but that doesn’t mean its pretty. Partial failures become an operational pain. CP systems react rather defensively to partial failures, since the system is design around safety first.

Real-World CP Systems

Let’s look at a few CP systems you’ll actually encounter or have already encountered.

etcd : The Backbone of Kubernetes

If you’ve used / played around with Kubernetes at all, you’ve used etcd . Whether you knew it or not.

etcd is a distributed key-value store designed for reliability over speed. It’s purpose is not to deliver high-throughput workloads, but rather for data that absolutely cannot be wrong. Things like configuration files, coordination, service discovery, etc. Small amount of priceless data that everything else depends on.

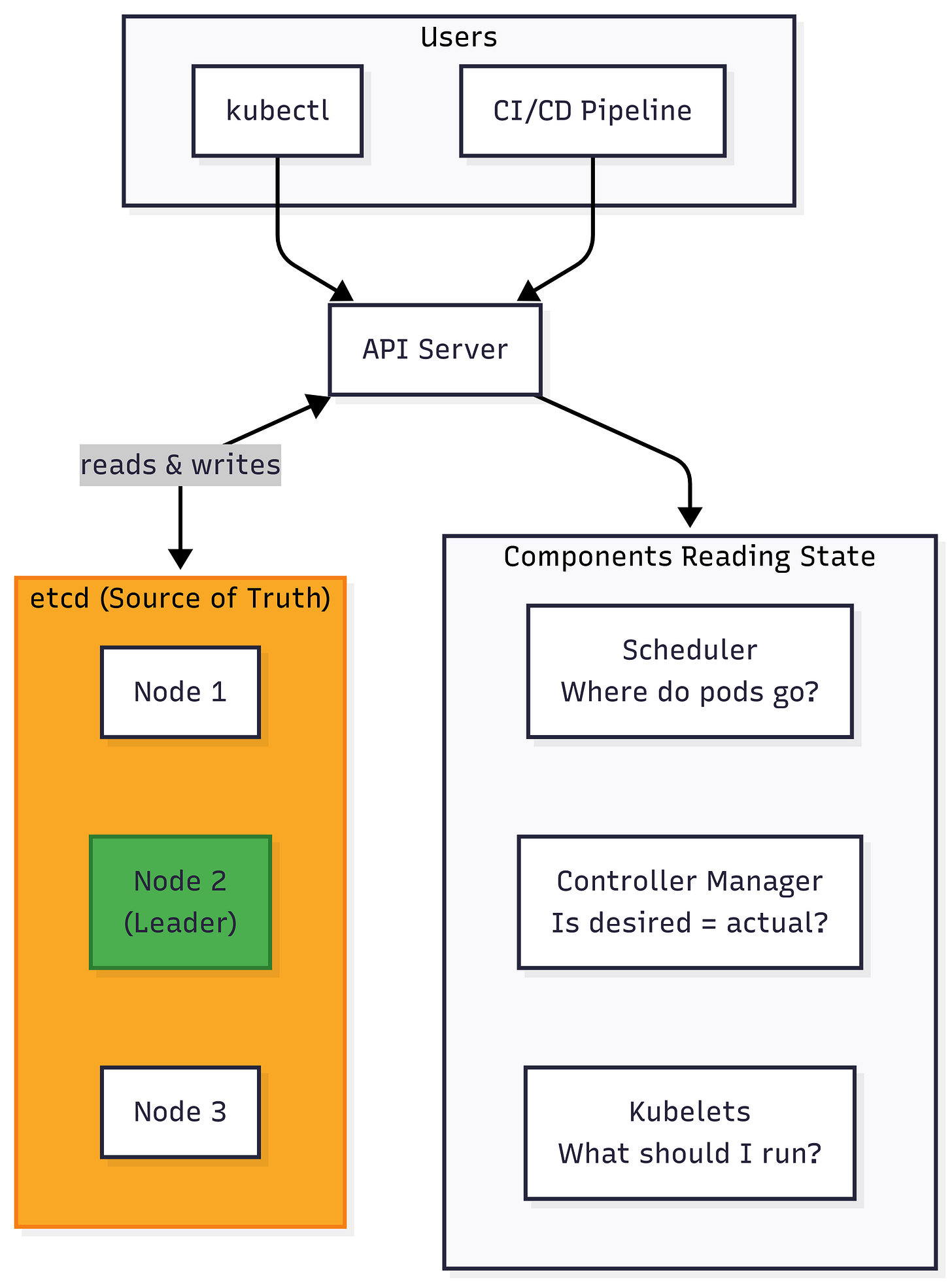

etcd is responsible for storing the cluster state: pod definitions, service configs, secrets, all of it. When you run a kubectl apply that manifest that you provide ends up in etcd. When the scheduler needs to decide where to put a pod, it reads from etcd .

Why CP?

Kubernetes needs a single source of truth. Every component of Kubernetes (the scheduler, controller manager, kubelets, etc) makes decisions based on what’s stored in etcd. If two nodes disagree about, say, which pods are running where, you get absolute chaos. Double scheduled pods, orphaned containers, screwed up service routing, and the failures snowball into a nasty ugly mess.

In these situations, would it make sense for the system to continue to serve inconsistent / wrong data? Or is it more beneficial for the system to stop for a little bit and straighten things out? etcd handles this by electing a new leader, that brief pause in availability is annoying as an end user, but it is infinitely better than an inconsistent system.

The Trade-Offs In Reality

Ever experience a situation where kubectl commands hang or fail during cluster instability? That’s etcd behaving like a CP system, as it was designed to be. If etcd can’t reach quorum, it’ll stop accepting writes. Your kubectl apply commands time out, it’s safer to deny the write.

I’ve faced this multiple times, whether its slow disk I/O, network latency, or resource exhaustion. Each of these can lead to failed heartbeat checks which, in turn, leads to leader re-election and suddenly the cluster become unresponsive. Slow writes hang, kubectl commands just hang. It’s annoying, but that’s the correct behavior as etcd is designed. etcd is protecting data integrity.

etcd uses Raft for consensus. This means that all writes go through a single leader node and require an acknowledgement from a majority before it gets committed. In the context of this post, etcd reads must also go through the leader node, since it’s the only one that knows what’s been committed. etcd also allows for serializable reads (must be configured this way) but, by default, etcd provides linearizable reads.

Zookeeper: The OG

Before etcd, there was Zookeeper. It’s much older than etcd and is the backbone for the coordination for systems like Hadoop, Kafka, and Spark. If you’ve used any of those systems, Zookeeper was running in the background keeping things in order.

Like etcd, Zookeeper is also a distributed key-value store. It’s a very specific KV-store (not worth getting into in this post, but fundamentally it only stores critical data) that handles mission critical data that is absolutely needed to setup and maintain coordination. Things like, who the current leader is, what the current config looks like, etc.

Why CP?

Much like etcd , Zookeeper maintains the coordination for a system. No two nodes should think they’re the leader, no two processes should both hold a resource lock, no node should be serving stale data once a write has been committed.

If those issues aren’t addressed you can run into split-brain failures, data corruption, or cascading failures. These aren’t failure modes that can just be ignored. Zookeeper, like etcd , was designed to address these very issues.

The Trade-Offs in Reality

Zookeeper has the same quorum related issues as etcd , for a 5-node cluster if you lose 3 nodes it stops entirely. No writes, no reads, nothing at all.

The problem with Zookeeper is the way it’s integrated. Zookeeper is often a dependency for other systems such as: Kafka broker coordination, Flink high availability, Hadoop for failover coordination.

So if Zookeeper goes down, your Kafka topic goes down, suddenly your event stream is down and your entire system stalls. All because one coordination system couldn’t maintain quorum.

PostgreSQL: Everybodies Favorite DB

Here’s a shocking on, PostgreSQL can be a CP system. Not by default, gotta make a few config changes but do that and it can behave like a CP system.

Out of the box, Postgres with async replication doesn’t completely fit into CP or AP. Writes go to a single primary. Stanbys replay the logs but don’t actually accept their own writes. If the primary dies before replication is completed, those writes are gone. But you never get wrong data. For many, this is fine. You accept the small risk of data loss for better performance.

But financial systems and booking systems can’t lose a single transaction. Situations where yolo-ing isn’t an option.

Making Postgres CP

In order to make Postgres into a CP compliant system we have to enable synchronous replication. Once enabled, every write will wait for at least one replica to confirm the write before the primary acknowledges the commit.

# postgresql.conf

synchronous_commit = on

synchronous_standby_named = <server_name>

That’s all it takes to make Postgres CP compliant. Your writes are now redundant across multiple nodes. If your primary goes down, a standby has everything needed to serve data. Zero data loss on a failover.

The Trade-Offs in Reality

Now that you’ve turned on synchronous commit, you’re waiting on the network for every write. If your standby is slow, writes are slow. If your standby is unreachable, your writes hang. You’ve successfully traded availability for consistency.

Many don’t really need this. You can get by with async replication with proper failover. But for those instances where losing data is just not an option, synchronous replication is how you address it.

MongoDB: CP If Configured Properly

MongoDB, a NoSQL DBMS that uses a document-oriented data model, can behave as both AP and CP depending on its configuration.

By default, MongoDB isn’t CP. By default, writes are acknowledged after hitting only the primary and reads are local which means it can be unreplicated.

writeConcern: {w: 1}

readConcern: "local"

This is fast, but it’s also how customers allow for weaker consistency guarantees than a pure CP system.

Making MongoDB CP

It only takes two settings to configure MongoDB as a CP system.

// WRITE: WAIT FOR MAJORITY OF REPLICAS

// per operation

db.collection.insertOne(

{ item: "widget" },

{ writeConcern: { w: "majority" } }

)

// per collection

db.createCollection("orders", { writeConcernt: { w: "majority" } })

// per client

new MongoClient(uri, { writeConcern: { w: "majority" } })

---

// READS: ONLY RETURN DATA COMMITTED TO MAJORITY

// per operation

db.collection.find().readConcern("linearizable").readPref("primary")

// per collection

db.items.withOptions({

readConcern: { level: "linearizable" },

readPreference: "primary",

})

// per client

new MongoClient(uri, {

readConcern: { level: "linearizable" },

readPreference: "primary"

}

With w: "majority" , writes aren’t acknowledged until they’ve been replicated to a majority of the replica sets. With the linearizable read option, reads only return data that’s been committed by the majority. With these two options we have strong consistency.

The Pitfalls

This has to be explicitly done. MongoDB doesn’t default to a strong consistency model. The cost of these changes are pretty significant, majority writes are slower and linearizable reads can only go to the primary.

When configuring MongoDB don’t assume a strongly consistent data model. If you need CP, configure it.

When Should You Choose CP?

CP systems aren’t better or worse than AP systems. They’re both perfect for different use cases.

Choose CP when:

Real-time consistency for shared state is a necessity. Financial transactions, inventory, etc. Anything where eventually being right is just not good enough.

Coordination is the primary driver. Like we saw, leader election, distributed locks, and config management are all driven by coordination.

The blast radius for inconsistencies is large. Disagreeing nodes causing cascading failures??? Choose CP.

Brief moments of unavailability are tolerable. Leader elections or network issues can cause slight outages.

Be cautious of CP systems when:

Availability is paramount. User-facing app where something is better than nothing.

Global write distribution is required. Strong consistency across regions increases write latency and can reduce availability.

Consistency requirements are weaker than

linearizability. Many systems are fine with causal consistency or read-your-writes. These system don’t require linearizability.

The question you should ask is this: “What’s worse? Being briefly wrong or briefly unavailable?”

If stale data can cause harm, lean CP. If refusing requests causes more harm, lean AP.

Up Next: AP Systems

CP systems buy correctness with latency, throughput limits, and occasional unavailability. But what happens when a system makes the opposite trade-offs?

In Part 3 of this 4-part series, we’ll take a look at AP systems, databases that stay available during failures by relaxing consistency.

How DynamoDB and Cassandra remain available during network partitions?

Common conflict resolution strategies

When eventual consistency is not just okay, but the right choice

and more.

The “pick two” framing makes distributed systems feel like a binary choice between CP and AP. Reality is a lot more complicated and the trade-off decisions are extremely interesting.

Thanks again for sticking around. If you enjoyed this post, consider subscribing, t’s what gives me the confidence to keep writing.

— Ali